This post is inspired by the presentation by Ashish Kaushal at London Value Investing Club. The content of the post, however, is the view of the author.

Humans have always considered some objects as assets. Food, shelter, clothing, water. These have value to people because they’re necessary to survive. Some assets, like gold or electricity, have value because they make our lives easier or more productive. Stocks and bonds have value because they allow us to share in the creation of further assets and wealth.

The survival assets are important for other living things, too, and therefore survival assets have been part of society since we first learned to communicate by grunting. The evolution of stocks and bonds as assets has been considerably shorter. However, even stocks and bonds have acted as financial assets much longer than more recent developments, like derivatives. Each of these groups falls into an asset class or a grouping of assets with similar pricing mechanisms and market behaviours.

How do these new asset classes arise? Cavemen were not trading stocks, and even the then-sophisticated 19th-century financiers were not trading credit default swaps and carbon credits. The evolution of technology enables greater complexity in our assets, and sometimes new technologies are the basis for new asset classes themselves. Sometimes scientific breakthroughs lead to new asset classes, such as the aforementioned carbon credits, which form part of the eco asset class; without the threat of climate change and the political impetus to curb it, there would be no market for trading carbon caps.

The Origin of Financial Asset Classes

Whenever something becomes useful for people, it becomes popular. And when something is popular, it has the potential to become an asset class. However, it is only when something becomes essential that it has achieved the status of an established asset class. Once a concept or object of value is indispensable, either to the survival or the efficient functioning of society and the economy, people will pursue ownership and the concept is embedded into the foundation of society and the economy.

The essential survival assets, such as food and shelter, were important and useful to people even before we were human. Commodities became assets when entire societies demanded gold jewellery or salt or oil. Debt and bonds became assets since we had easily transferrable money, and sovereigns became assets when governments needed to fund wars they could not afford through their own coffers. As the industrial revolution rapidly increased complexity, we needed other ways to represent wealth and ownership: thus arose the company stock. Scientific discoveries, like that of electricity, uncovered new ways to generate and store wealth. Some inventions parlay into new forms of assets under already-established classes: electricity was eventually commodified, and today it belongs to the asset class of commodities.

Overview of the Origins of Specific Popular Classes

Bonds

Bonds have existed for millennia. The first bond with extant evidence comes from Mesopotamia in 2400 BCE. The next step took three millennia, but a public bonds market developed in Venice, Italy, in the 1100s. The impetus? Government borrowing for war funds.

Options contract

Aristotle described an options contract in his Politics, but it was not standardized or traded. Some of the earliest modern-era futures were traded on the Dojima Rice Exchange in Osaka, Japan in the early 1700s. London, as the seat of one of the world’s most powerful empires, saw metal trading in the late 1800s, and the rise of agricultural production in the American Midwest saw the explosion of Chicago as a futures trading centre. Other derivatives, like Credit Default Swaps, arose with financial deregulation and the increase of computing power.

Equity

Equity, as a share of economic endeavours, has existed since Ancient Rome. There were various divisions of economic activities and the profits thereof, but the first tradable corporate equity is usually traced to the Dutch East India Company’s stock issues in 1602. As urbanization swept Europe and North America in subsequent centuries, more centralized occurred and official exchanges sprang up, eventually leading to the large organizations we have today.

Survival, economic and societal utility, government projects and later corporate and personal projects, and technological and scientific advancement are the reason new assets arise. If something is essential or massively improves efficiency to the point anyone operating without it is severely disadvantaged, and therefore it is essential by relation – imagine how successful a business that eschewed electricity would be on the global stage – it certainly becomes an asset and possibly a new asset class.

Recent New Assets

Some recent asset classes to have been created, discovered, or invented include carbon credits, data, cryptocurrencies, and computing power.

Carbon Credits and Environmental Assets

Environmental assets have the potential to become a new asset class. They are not usable in the sense of commodities, and their value is largely derived from synthetic sources, such as emissions predictions. A potentially interesting and new pricing mechanism for this asset class is a global IoT-connected sensor network that tracks the environmental impact of the economy in real time. One of the most famous assets from this class is the carbon credit.

Carbon credits are not essential yet, but they may become so in the near future, as governments become ever more fearful of the effects of climate change. This need for companies to either pay for the externalities via carbon credits or reduce their carbon dioxide emissions may eventually make carbon credits an asset class: they are required by all companies, but they are not like other assets in pricing mechanisms or source.

Data – corralled by the few

Data creates significant wealth and power for those who control it. It is generated by everyone and everything, but only a few corporates and governments can effectively leverage its power. Data would be a kind of restricted asset class, and while it isn’t vital to efficient economic functioning now, it gives an incredible competitive advantage to those who can capture and manipulate it.

Cryptocurrencies – for the masses

Conversely, cryptocurrencies are meant to be open to the masses, and anyone who wants to join is able. The ability to enter this asset class was made evident by the runup of prices in December 2017 and January 2018, as even the nearly financial illiterate started to trade Bitcoin and altcoins through smartphone apps during their commutes.

Computational Power and Digital Storage

Some assets, such as computing power and storage, can be rented and divided like stock or real estate, but they certainly behave in different ways and have different metrics. One might rent 50Ghz of processing power for 30 minutes or 500TB of storage for a monthly fee, where this time is used for further creation. At this point, storage has been commodified, but distributed computing power is still not quite a commodity.

Other possible future asset classes that could arise from current scientific and technological pursuits include AI and biotechnology like periodic age deceleration (maybe a monthly injection mitigates ageing, where the injections are traded on a black market). There is no reason that asset classes must originate in the financial world, and in fact, it seems most of them arise from societal or scientific realms before the financial world securitizes and standardizes them for their efficient trading and implementation in business.

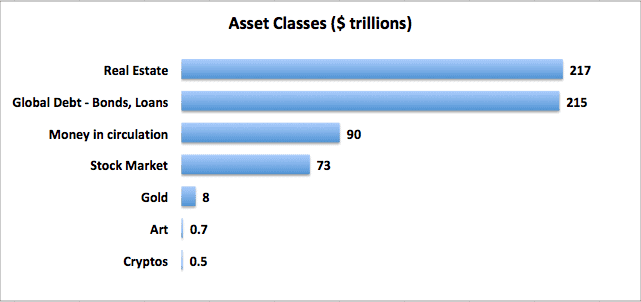

As you’d expect, it’s not easy to quantify the different asset classes on a global label, but below is our estimate from various online sources.

Future Classes

As noted above, asset classes stabilize when they become essential to society. One way to predict new sources of asset classes is to understand current problems. A new technology or idea that makes significant progress in solving a problem has a high potential to become an asset, and if the idea or technology is sufficiently original, there may even arise an entire asset class.

Some of today’s problems, such as climate change, have given rise to the aforementioned environmental asset class. Carbon credits are just one example. Air, water, noise, and light pollution may also come under governmental regulation, and if economic incentives are levied to encourage pollution reduction, we could see cities offering certificates to buildings that turn off their lights at night. Eventually, those certificates may be traded to other real estate owners who wish to keep their lights on but do not want to pay a high penalty for it.

Beyond environmental concerns, human society is riddled with problems. Poverty, hunger, and violence are as old as humanity itself. Distribution networks that efficientize the delivery of medical supplies and food to natural disaster zones may become an asset class, possibly arising from existing infrastructure and new delivery methods, like IoT-connected drones. As the technology improves, these new networks could be adapted for times when disasters are not ravaging the area. Smart cities springing up in India, China, and South Korea may already have started to implement a new kind of distribution and connection network that will prove immensely valuable in the future.

Some technological breakthroughs might actually destroy asset classes. A good forward-looking example is energy. Were scientists to finally build a sustainable and efficient fusion reactor, our energy problems would evaporate. An overabundance of energy may lead to new problems, but the ageless struggle for sufficient energy sources, including the war and strife involved, would at least transform.

The Cryptocurrency Question and a New Class

Cryptocurrencies are quite popular today. Are they essential? Certainly not. Do they have enormous potential to become an asset class? Certainly yes. Traders, the media, and the public at large have latched on to this new asset class, but will it become dominant? Some, like Warren Buffet, believe cryptos will collapse or wither. Regardless of whether they go out with a bang or a whimper, cryptos will no longer be around in the future. We at CityFalcon don’t think Bitcoin will remain the predominant cryptocurrency either, though we are much less reserved than Buffett on the death of all cryptocurrencies. Yet others, like the Winklevoss twins of Facebook fame, think Bitcoin will become “a multitrillion-dollar asset”. With a current market cap somewhere north of 50 billion but under half a trillion – the large uncertainty is due to price swings – the Winklevosses certainly believe the currency will continue to grow. And if Bitcoin fails, there are literally hundreds of other coins poised to take its place.

While it seems futile to attempt to predict the future value of cryptos, just as an 18th-century equity investor would be unable to predict the massive scale of equities today, we can see that cryptos will become an asset class, not just another commodity or currency.

This is due to the inherent and differentiating properties and advantages of cryptos. One such example of this differentiating property is the smart contract. On the Ethereum platform, among others, the cryptocurrency itself is used to power distributed applications and agreements written into code. Clearly, currencies, like the GBP, do not offer this embedded digital application. Digital representations of fiat currencies are simply that: digital representations. They boast no additional factors, like embedded software code. Commodities may have software implementations, but they cannot double as currencies. One such example is electronic distributed storage (the cloud): it’s been commodified through its extensive availability, but it is very rarely used as a store of value, as a currency is. Few people trade terabytes of storage space to transfer value, because which storage is important: as data must physically reside on hardware somewhere.

Another characteristic vital to the differentiation of cryptos as a separate asset class is the possibility of tokenization. With smart contracts and cryptos, almost anything can be tokenized. In fact, tokens may become a separate asset class in themselves, though they will require some sort of blockchain and base cryptocurrency for their functioning. Services like car-sharing may come to be represented through tokens, where a driver is paid in tokens that are convertible to cryptos, and customers can trade tokens amongst themselves. This highly specific use of tokens makes them less broadly useful than cryptos, but their potentiality arising from cryptos does provide the differentiating factor to make cryptos a separate asset class.

The Value of Cryptos

Price and value are not identical. This is especially evident in cryptocurrencies. The value of the technology to society does not fluctuate considerably on an hourly basis as the price does. Some months the price may skyrocket and others it may plummet, but the value does not follow suit.

So how do we ascertain the value of cryptocurrencies? The value of an asset derives from its usefulness to people. The concept of cryptocurrencies is immensely valuable, as it eliminates a large number of middlemen and increases efficiency in that regard. Of course, the technology has plenty of growing pains to deal with, especially in scalability and security, but cryptocurrencies and their underlying technology, the blockchain, are highly likely to add value to society.

However, we already have assets that perform the main function of cryptocurrency: fiat currencies. There are definitely features bundled with the former that are not present in the latter, but there is stability and centralized control over the latter. Economic growth and stability is dependent on the stability of a means of exchange. Therefore, widespread adoption for cryptocurrencies is only likely with government support. Without government backing, there is little incentive for the average citizen to regularly use cryptos. With the immense power connected to controlling the money supply, it seems governments are unlikely to support the usurpation of fiats by cryptos.

That does not mean cryptocurrencies are doomed. Global household wealth was estimated at about 280T USD in 2017, and in just the derivatives market itself, there may be over 1Q USD (that Q is for quadrillion). Including the value of commodities, machinery, and assets not traditionally owned by households, the number is certainly in the quadrillions. There is plenty of room for more wealth in the world, and cryptos are only a small fraction of the total. Simply because cryptocurrencies don’t replace fiat currencies does not imply they will become valueless. The tokenization aspect of cryptos is especially promising for specific applications that lend value to the new asset class.

What the Future Holds

What the future holds for technological, scientific, and societal progress is unknown. It required centuries of development before debt was formalised into financial assets, and it wasn’t until the early modern era that the first true stocks arose. Derivatives, while they existed in the form of precursory futures in the 18th century, their standardization and widespread trading, and thus recognition as an asset class, also required hundreds of years.

It seems we have at least one set of tradeable objects that clearly defines itself as a separate asset class (cryptocurrencies) now. Whether the asset class itself will morph into a subset of another class (specifically, currency or commodity) remains to be seen. The emergence of new asset classes is inevitable. Sometimes it may take millennia, and other times it may only take decades, but as long as humans and society exist, there is potential for the emergence of new financial asset classes.

13/02/2018 at 1:07 am

Hey Ruzbeh, great history of asset classes. I agree that cryptos have the opportunity to become it’s own asset class. In addition, I think major corporations will start to accept cryptocurrencies other than bitcoin to buy everything from food to walmart phones. Once more major retailers come on board, there will be no stopping the crypto rise.

27/04/2020 at 3:51 pm

Thank you very much. All the facts explained by you are very simple and easy.

04/09/2020 at 4:50 am

Really this Blog is too Good and Very Informative. All you wrote about facts are too easy. Kindly Share more Articles.